Delenguaamano-Collective

Pinacoteca de São Paulo

ArtNexus #73 – Arte en Colombia #119

Jun – Aug 2009

São Paulo, Brazil

| Julia Buenaventura |

Every monument has a front, and with that front a direction in which we are going, and with that going a whole that is not singular but plural. In sum, a first person plural characterized by a future that is as shared as it is certain. The monument to Ramos de Zepeda erected in 1934 in front of the Pinacoteca de São Paulo was a clear example of this. With large dimensions and long-lived materials¿granite, bronze¿it attempted to establish a point for the city that would raise not as much the past, supported on Doric columns, but its future, represented by an advancing arm. However, it didn¿t last long: in 1967, due to the construction of the city¿s subway system, the monument had to be dismantled, then dumped, and finally re-erected away from its original site.

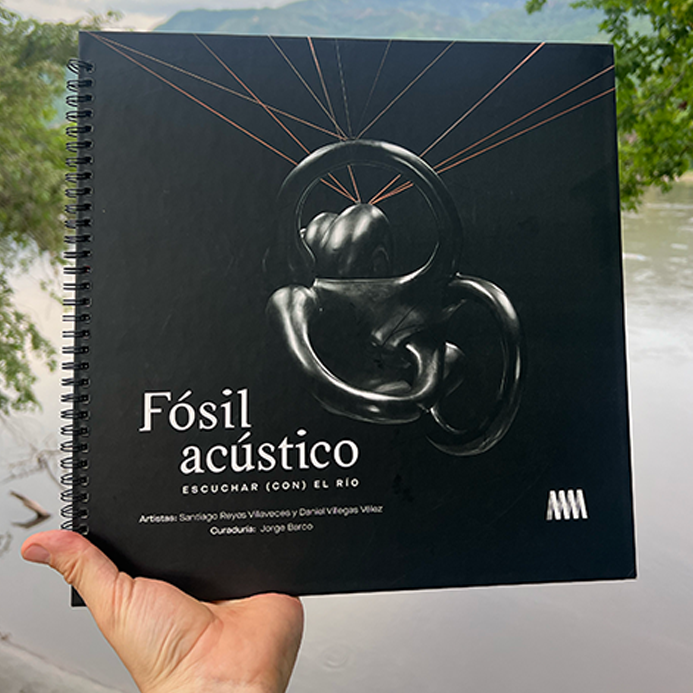

During the months of March, April, and May of this year, at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, the Delenguaamano collective¿comprised of Gilberto Mariotti, Néstor Gutiérrez, and Santiago Reyes Villaveces ¿took it upon itself, in its temporary shoe Monumetría, to once again raise that monument in a here¿the original location given to it¿and a now¿our own times.

The problem was that very little was left of the monument¿s here, and the same goes for that now, our own times: only unconnected pieces that do not indicate a destiny, mismatched, incapable of organizing a path of any kind. And it is precisely there, on that dislocated here and now, that Delenguaamano set the basis of the monument.

Monumetría was a single work/intervention divided into four parts: Perspectiva y proyección, a transparency; Mnemocine: a museum fragment; Trabajo y reproducción: a printing of postcards; and Reconstitución, a bronze casting. Four parts that feed on each other through two concrete actions: pointing to fragments and inventing coordinates.

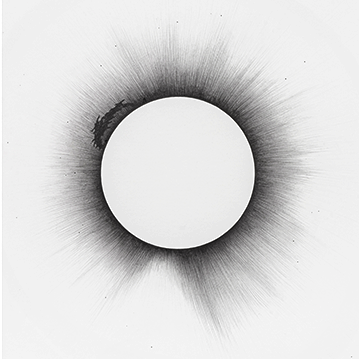

The first section, the transparency projection, comprises a small image of the sculpture arranged on a glass door. The door, which today opens to a small balcony, was once the Pinacoteca¿s main entrance and overlooked the square where the monument was located and met it from the back, since under no circumstance could they¿building and monument¿have been conceived front to front. Which is logical, since both had to be directed in a single and common direction: towards the future.

Delenguaamano¿s reinstallation didn¿t follow the original plan; on the contrary, the sculpture ends up turning towards the building, so that they now stand face to face. This is arranged in a simple way: thanks to its small size¿this is to say, by virtue of a classic trick of perspective¿the image of the monument moves away, leaving the building, establishing a distance, in order to return to its place yet not in its original orientation, but in a 180-degree turn. And with this turn the work¿s extended arm ends up simply pointing to the viewer, whose feet are on the ground of the building¿s former entrance¿its entrance from a time when the building still had a front, a trajectory, and a monument.

And there is something else. The glass door that supports the projection is one of those doors with sensors, so that as soon as one comes sufficiently close, it opens, the image dissolves, and the projector¿s beam continues on its way to nowhere.

What follows, or what I have determined follows, because there is no route here, is Mnemocine, a fragment of an exhibition. A temporary wall with artworks arranged as they would be in a history museum, not in a Twentieth Century arts institution. Firstly, because there are too many: over 130 in a twenty-by-four meter area; secondly, because these artworks are not claiming a private, isolated, or autonomous space, but rather intertwine with each other without any trouble. The viewer remains there, in front of these elements, recognizing some, being surprised by others. And it is in that interval that some tensions start to appear, due to the combination of very different subject matters: original works; original works that are copies of other original works¿Millet¿s The Gleaners in Anita Malfatti¿s version; photographs; fragments of photographs; artworks and their photographic reproduction; sculptures and objects.

In this way, a fracture begins to emerge under a harmonious and even decorative arrangement, a fracture that resides on the incompatibility of genres, in the impossibility of establishing a common denominator for that series of elements. And it is on that fracture where the 130 artworks will remain, unable in all cases to form a whole. In sum, the whole here is as frayed as the route.

But despite this, a constant is woven through the objects on exhibit, something that is not genre-related, formal, or conceptual, but thematic: the work itself. The fragments refer to people working, to hands holding tools, works of art as allegories of toil, photographs of those laborers who physically produced the tribute to Ramos de Azevedo. Labor becomes the communicating thread for the selection of objects. A rather singular thread for being a theme-related one, precisely that which a good part of Twentieth-Century art fled as soon as it said goodbye to monuments.

From there we move to the show¿s third and fourth sections: Trabajo y reproducción and Reconstitución, which is to say, to the postcards and the bronze casting. The postcards show passages of the construction of the monument, devoted to the laborers: the postcard¿s size matches the size of the original photograph, yet the only thing we see of the latter is the portion where the laborer is. This results in a contrast between the printed space and the white space, between what is shown¿in this case, the laborer rather than the result of his labor¿and what remains hidden.

And finally, the bronze casting. Delenguaamano re-melted a fragment of the monument, specifically the hand of one of the allegories that supported its base. This hand is holding a hammer. The fragment, however, is not presented as a final product; on the contrary, the whole process of its manufacture is on display, as the molds and overmolds required to build it are shown. A five-step process, a lesson in bronze-casting, and, at the same time, a parenthesis in time: these steps inhabit a same segment of time. These steps are not steps: they are going nowhere. They retrace themselves, without any established path. In the same way the monument to Ramos de Azevedo¿also called the Tribute to Progress¿doubled back on itself and ended up there, perplexed, looking towards the Pinacoteca and noticing that it had also turned.

Julia Buenaventura